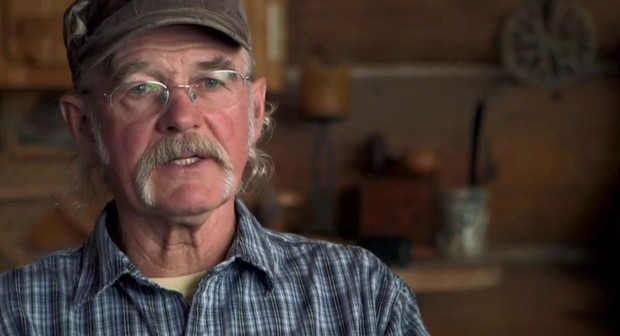

Sad😥😥 News! Alaskan The Last FRONTIER Atz Kilcher Very Hardly Car Accident!

The Enduring Spirit: An Alaskan Homesteader’s Reckoning with the Wild

The Alaskan wilderness is a landscape of uncompromising beauty and stark survival, a truth Ats, a seasoned homesteader and patriarch, knew intimately. Yet, it took a near-fatal fall from a cliff near Otter Cove—a moment when the ground betrayed him—for the wild to reveal its deepest, most profound lesson. The accident, which left him with a broken ankle, hip, shoulder, crushed ribs, and punctured lungs, stripped away the illusion of his own unquestioned strength.

The text opens with Ats in his Alaska Wilderness cabin, settling down for a simple evening meal. But this domestic scene is a hard-won peace, set against the backdrop of a life forever altered. The narrative quickly shifts to the raw, jagged memory of the fall—a summer day turned deceptive nightmare. The same land that had been his home suddenly felt like a conspirator in his downfall, leaving him in a sterile hospital bed, far from the familiar scent of pine and woodsmoke.

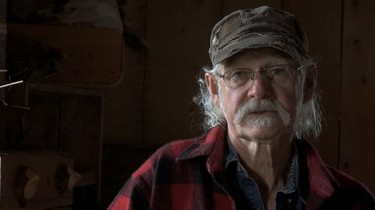

The Return and the Reckoning

Weeks later, he returned to the homestead, welcomed by the creaking porch wood and the silent, steady embrace of his daughter, Jewel. His recovery was not a swift, heroic montage, but a deliberate, painful process. Each day demanded a conscious effort, a protest from a body that was once infallible. He moved with a carved walking stick, performing the familiar homestead tasks—feeding horses, gathering wood—listening to the land that seemed to welcome him back with a quiet rustle.

One evening, standing under an old spruce, Ats whispered, “I’m still here. I’m still your son.” It was a profound moment of connection, an admission that survival alone was not enough; he yearned to live. This internal work continued, shared in a silent, meaningful moment with his wife, Lenidra, who confessed, “You scared me,” to which Ats admitted, “I scared myself.”

Gravity, Grace, and the New Song

As winter descended, Ats retreated inside, his physical mending accompanied by a spiritual one. He spent his time mending tools, carving, and, most importantly, writing songs—songs about falling and rising, about gravity and grace. These new lyrics were stripped bare, a raw testimony: “I fell down the cliff / I heard the rock cry / but the trees held my hand / and brought me back to life.” When he played it for his family, the message was clear: his scars were not mere badges of honor but proof of his return.

By spring, the melting snow mirrored his own thaw. He ventured out again, lighter and stronger. His ultimate act of healing was to stand at the cliff’s edge where he fell, looking down at the swirling water. The fear remained, but it no longer held him captive. He laid a hand on the cold stone and whispered, “Thank you, for the lesson.”

The experience taught Ats that the wilderness is not merely scenery; it is character. It breaks you, but it also holds you. The camera of reality television, which often captures the physical labor of Alaskan life, frequently misses the soul work. He learned that being tough meant being honest, and being open meant being strong.

Sitting on his porch, watching the mist rise, Ats found his peace. He was home, not just in the log cabin or on the familiar land, but home in the self he had almost lost. The wilderness, he concluded, is neither forgiving nor cruel—it simply is. It holds you or it lets you go, and in the end, Ats had been held.